It sounds like science fiction, but it's terrifyingly real: a nation is preparing to mine the deepest ocean floor.

This coming January, Japan will begin the world's first test of full-scale deep-sea mining near Minamitori Island in the western Pacific. Until now, the abyssal plains of the ocean have only been visited by scientists. But this project, spearheaded by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, plans to extract critical metals from 6,000 metres deep to extract “rare earth” elements by hoovering up mud from the seafloor.

Even before it starts, marine scientists and campaigners are sounding the alarm. Japan’s government is proceeding despite warnings that this activity will inflict “irreversible harm to ocean ecosystems.” Environmental groups bluntly describe it as unleashing a Pandora’s box: industrial operations on the seabed will cause “irreversible biodiversity loss”.

This may affect all life on Earth as we know it.

If successful, Japan won’t just be the first country to harvest these minerals on a commercial scale. It will also open the floodgates to one of the most dangerous and underregulated extractive industries on Earth.

The trade

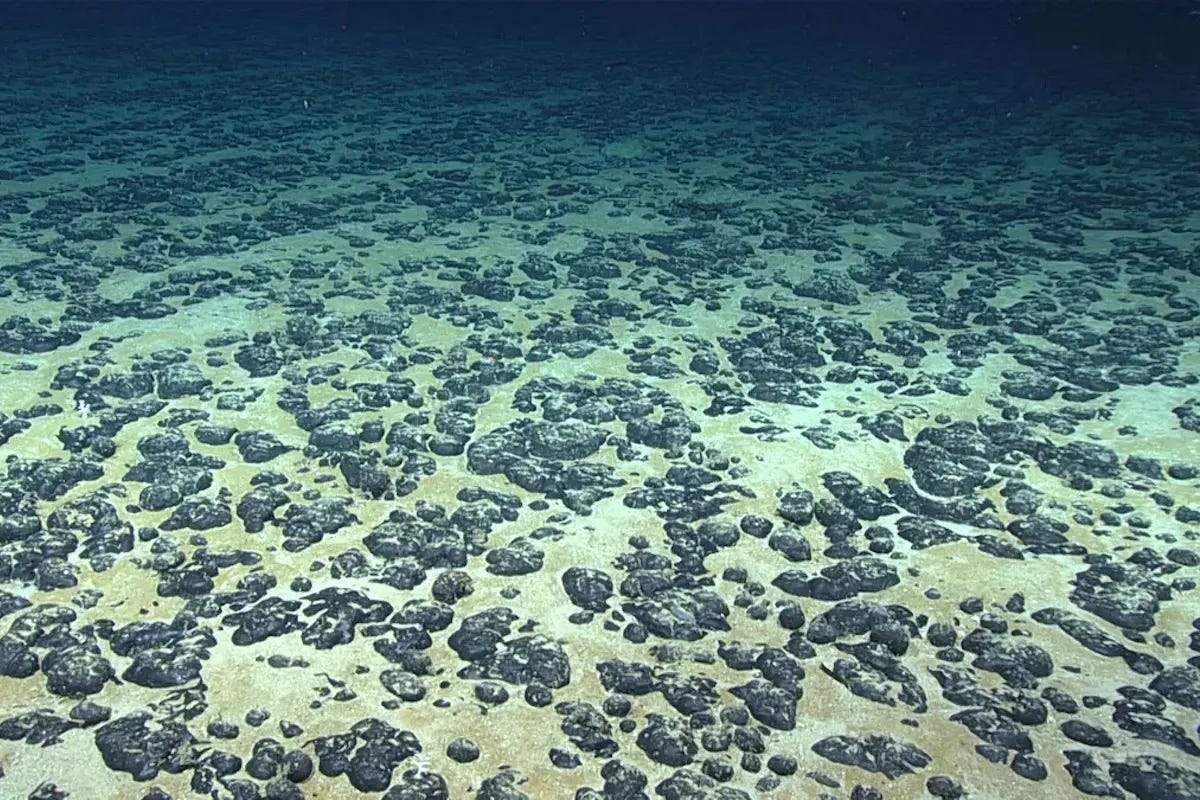

Deep beneath the waves lies a fragile world. On the abyssal plains – cold, dark and far from sunlight – strange creatures cling to polymetallic sand and manganese nodules.

Japan is now ready to rip open this world. By January, a Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) vessel will start sucking up mud rich in metal nodules. In the first phase it could process hundreds of tonnes of mud per day by 2027, isolating critical metals like dysprosium, neodymium and terbium for electric vehicles.

Officials say this is about national security, securing “stable supplies of critical minerals” in the face of export controls. But we think that trading a living ocean for more EV motors is lunacy:

Until now, deep-sea missions like this have been scientific, turning them commercial could literally end life as we know it.

A discovery that changes everything: The rise of Dark Oxygen

In 2024, scientists studying deep-sea nodules stumbled upon a discovery that could rewrite our understanding of how life on Earth survives, and how it all began. These nodules are producing oxygen in complete darkness.

This phenomenon, dubbed "dark oxygen", appears to be caused by natural electrochemical reactions between the metals in the nodules and surrounding water.

In short, these nodules act as underwater geobatteries, splitting water molecules to release oxygen and hydrogen. It's a process unlike photosynthesis and potentially a key element in how deep-sea ecosystems breathe.

What happens if we remove these oxygen-producing structures from the ocean? We simply DON’T KNOW. But the implication is horrifying: we may be about to dismantle an oxygen-generating system we never knew existed, a system that may be critical to regulating life in the ocean and possibly on Earth.

Playing with fire: Drilling into the Earth’s tectonic plates

Japan’s technological edge makes this disaster possible. Its deep-sea drilling ship Chikyu is built to bore through the ocean floor into the Earth’s mantle. As engineers brag, Chikyu’s special mission is to drill the deepest hole ever. In practice, that means the vessel can penetrate the oceanic crust and reach the underlying rock layers.

We are talking about punching kilometers-long holes into a tectonic plate. The Earth’s crust is broken into plates whose movements cause earthquakes and volcanic activity. Who knows what could happen if we start blasting into those stable undersea crusts? In worst-case scenarios, we could trigger underwater landslides, methane venting or even new volcanic eruptions, essentially poking a stick at a sleeping dragon.

The deep seafloor is alive with geological forces; mining it is a wild gamble with nature’s mechanisms that humankind barely understands.

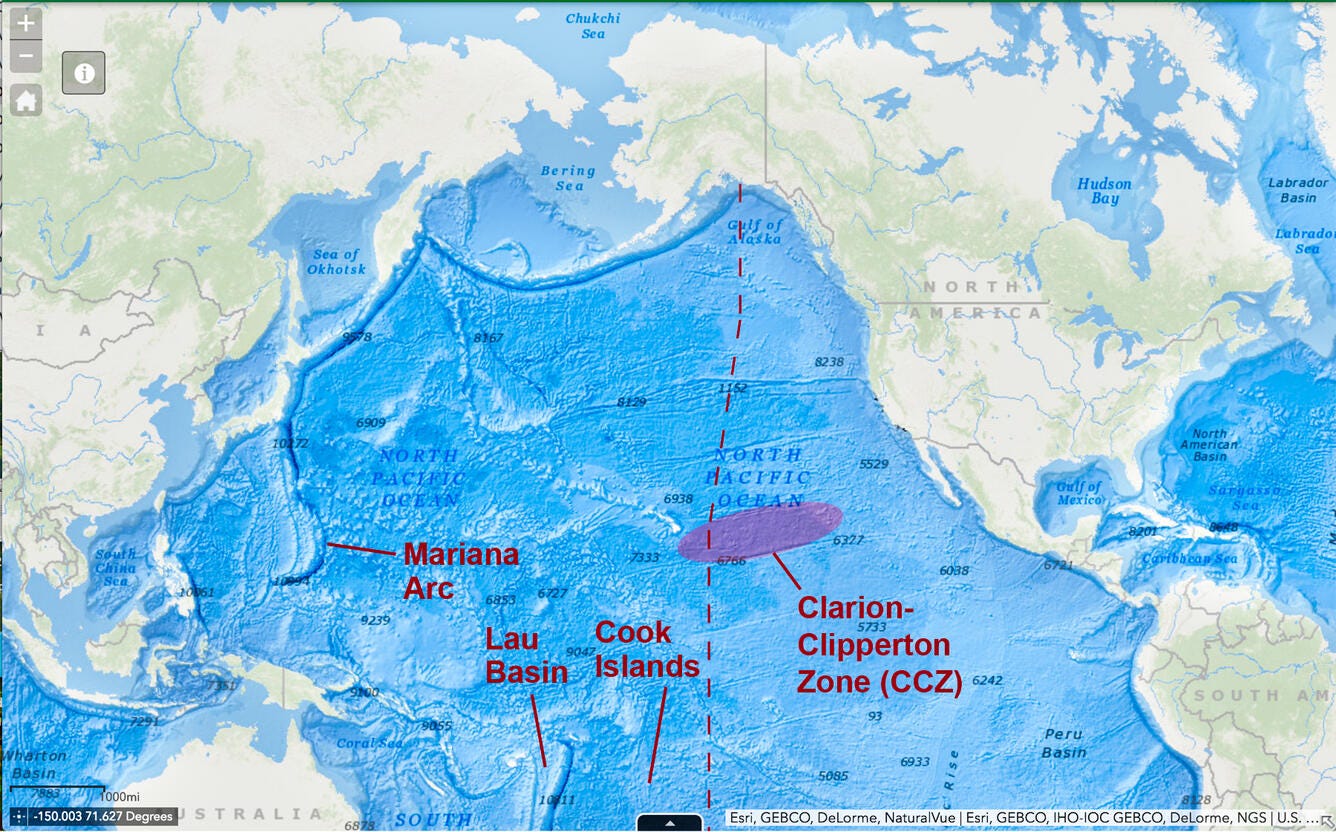

The global race and the Clarion-Clipperton Zone

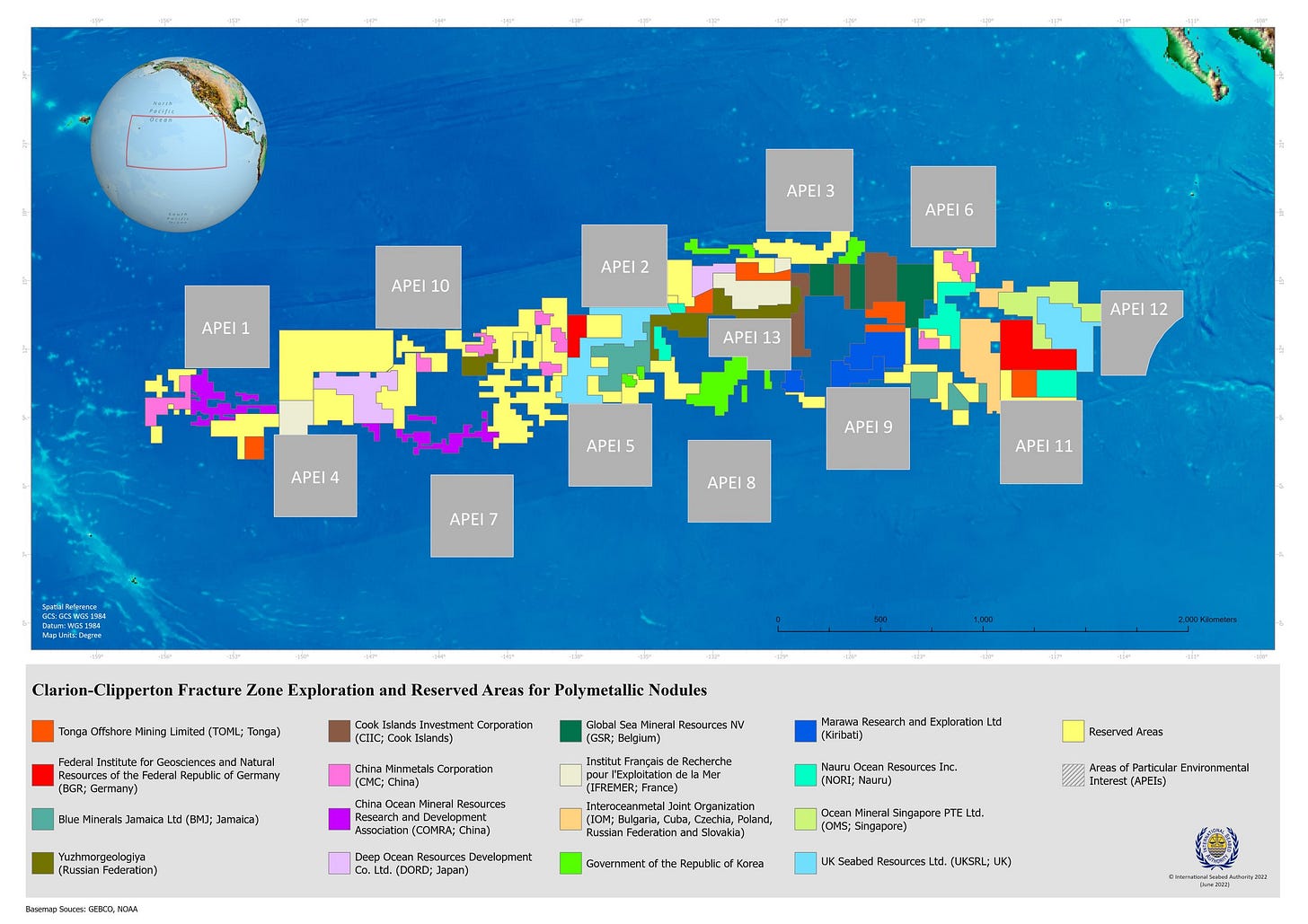

Japan is not alone in this race. Around the world, governments and companies are scrambling to profit from the ocean’s last untouched frontier. Countries like China, Russia, India, France, the UK, and Germany all hold exploration contracts for deep-sea mining in international waters (these contracts authorize them to investigate, though not yet exploit, mineral deposits) through the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an obscure UN-affiliated body based in Jamaica that regulates deep-sea mining in international waters.

In the USA, the mining firm The Metals Company asked the administration to approve mining outside US waters, and President Trump issued an executive order “aimed at boosting US access to critical minerals” by jump-starting ocean mining.

Even oil majors like Glencore are gearing up to buy minerals from the seabed. With political support from nations eager to get these metals, the pressure to begin mining is enormous.

In short, it’s a modern-day gold rush beneath the waves: all the countries of the world are gunning for the nodules on the ocean floor.

Yet ironically, many of these same governments profess concern for climate and nature. It’s a bitter irony: in order to make electric cars and wind turbines “clean,” we’re talking about ruining the one ecosystem that absorbs carbon and regulates our planet. We are treating the deep ocean, one of our greatest allies in combatting the climate crisis, as a dumping ground.

The only sane response is a global pause.

Where do they all want to start? One of the most hotly contested and dangerously targeted regions for deep-sea mining is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

Stretching across 4.5 million square kilometres of the Pacific Ocean, this huge abyssal plain is home to some of the richest known deposits of polymetallic nodules on the planet.

The CCZ is not just a geological treasure trove; it is an ecological frontier. Scientists have barely scratched the surface in understanding the biodiversity of this region. Thousands of species, many endemic, have been discovered in recent years, yet most remain undescribed. The removal of nodules in this zone doesn’t just mean stripping away metals; it means annihilating entire ecosystems before we even know what we’re losing.

Mining the CCZ would mean extracting nodules over areas the size of countries, with sediment plumes and noise pollution reaching far beyond the extraction zones. It’s not only a threat to benthic life but to migratory species, carbon cycling, and the global climate.

The ISA: The obscure authority governing the deep

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is a little-known UN-affiliated body based in Kingston, Jamaica. It was created under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to manage mineral-related activities in international seabed areas, areas beyond national jurisdictions, often referred to as "the common heritage of humankind."

In practice, the ISA has operated with limited transparency, questionable accountability, and a disproportionate influence from mining interests. Despite its mandate to protect the marine environment, it has granted more than 30 exploration contracts, covering over 1.5 million square kilometres of ocean floor, mostly in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

Many scientists, environmental organisations, and even member states have criticised the ISA for sidelining precautionary principles in favour of industrial pressure. Its meetings are often closed-door, with minimal input from civil society or affected communities. As commercial interest intensifies, the ISA is now under immense pressure to finalise mining regulations, potentially opening the doors to full-scale exploitation without proper environmental safeguards in place.

The fate of the deep sea is being decided by a handful of delegates behind closed doors, and most of the world has no idea it's happening.

The ocean is not ours to destroy

This isn’t just a mining issue. It's an existential crisis. The ocean is the planet’s largest carbon sink. It regulates the climate, provides more than half the oxygen we breathe, and sustains all life. Damaging the deep ocean means undermining the very foundation of our biosphere.

Unlike land ecosystems, which can sometimes recover within decades, the deep sea has recovery times measured in millennia. Mining it means a permanent loss of biodiversity, of species never named or studied, of biogeochemical processes we do not yet understand.

This includes the potential collapse of microbial systems that detoxify the ocean and regulate climate feedback loops.

Many countries, scientists, Indigenous groups, youth leaders, and ocean defenders are demanding a moratorium on deep-sea mining. More than 800 marine science experts from over 44 countries have warned against it. Over 37 governments have called for a precautionary pause. And yet, Japan, without waiting for international consensus, is forging ahead.

What you can do

Raise awareness. SHARE this story. Use your voice to spread the truth about what deep-sea mining really means for the planet.

Contact your representatives. Urge your government to support a global moratorium on deep-sea mining. Demand transparency and accountability at the International Seabed Authority.

Support ocean defenders. Donate to or volunteer with groups like Seaspiracy trying to stop this insanity and educating the world.

Demand ethical tech. Become a conscientious consumer and push for recycling and ethical sourcing of minerals. Support innovation in battery tech that doesn’t rely on seabed destruction.

Join the movement. Sign this petition before it’s too late. Make sure they know you opose deep-sea mining.

If you’re a member of an Indigenous group, you can sign this petition calling for a ban on deep-sea mining.

If you’re a marine scientist or policy expert, add your name to the Marine Expert Statement Calling for a Pause to Deep-Sea Mining here.

THIS IS NOT A DRILL.

The deep sea is not a resource colony. It is a living, breathing, ancient world. And it may just be the planet’s last line of defence. If we destroy it, we destroy ourselves.

The time to stop deep-sea mining is NOW.